CW: these are uncensored reactions to animal slaughter on a small farm in Western Maine. There are uncensored photos also. Definitely do not read this if the word “slaughter” was rough: i need to get this all out. i have no reason to be doing or writing about this other than a relentless desire to fully understand all of life.

Today we wrangled ducks. Mostly i just herded. All the geese and lady ducks were shooed away to leave a flock of eligible bachelors. They all fussed a lot, but i haven’t ever seen these birds not fussing. They are loud and skittish. The farmer crouches to stare at the useful bodies all huddled. He takes his time. Focusing on one bird is like playing the shell game: the ducks clamor just a bit and you can’t tell which one you had in mind. He finds the breeding male for next year, tags him, then releases him to the flock. i told that drake he didn’t know how lucky he is. He doesn’t, because ducks are birds. In theory, this shouldn’t invalidate their worth, but only in death do they attain value for the man who raised them. So today, we wrangled four drakes from the flock.

All of the ducks and geese were clearly uncomfortable as we did this. Whether they understood anything is debatable, at best. Half to cope, i thought to myself, “Life isn’t all it’s quacked up to be anyway.” i laughed aloud, unheard among the nervous din, and thought about how maybe i wasn’t just coping, because that was a great joke.

Farmers handle animals like a belonging that refuses to. Like a child they don’t care to communicate with. When i ask him if he does communicate, the farmer here says, “I never stop thanking the duck. I thank it the whole time.” He teaches me to put the bird to sleep by forcibly tucking the head under a wing. It works, and i carry one duck to the cage on my own, out in front of me like a heavy rugby ball i’m a little afraid of. i want to hold it closer but i’m not trying to wake it up.

The process isn’t surprising. We take the caged ducks away from all of the other animals and cover them with a tarp. Knives are sharpened, water is boiled, and the farmer listens to sea shanties as he prepares. This is his thing. The birds go upside down into a metal holder not unlike a funnel. There is a bucket underneath.

i watch the first bird until the end, it’s white-feathered neck bleeding out from a nicked artery while firm hands hold steady, stilling the nerve-filled body as the blood flows down. A friend like me might notice that the level of concentration given to this task is one rarely seen from this person. He doesn’t look like an artist rendering beauty; he simply looks focused, and natural. He lets go after a time; i knew there would be twitching. It wasn’t nice, but i didn’t experience the full-on heebie-jeebies i’d expected. i didn’t flinch, or make any more jokes.

It occurs to me after a time that i am witnessing deaths, in succession. i examine myself for any signs of duress. i come up empty. There is nothing poetic or romantic about this. i am struck, in fact, by the lack of drama in general. This is an uncomplicated thing; true. There is more truth here than i seem to have experienced in quite some time. It isn’t good or evil or difficult or easy. It is actually simple, honest labor. Quiet.

After they’ve bled out, the ducks need to be scalded, not boiled, but heated slightly so that their feathers might more easily be plucked. They don’t seem easily plucked to me. This is repetitive, visceral, and a fluffy weird mess. There are downy white feathers flying everywhere with a darkly ironic whimsy.

“I never thought I’d be so appreciative of plastic sheeting,” this man is excited to tell me about all of his tools. Proud and glad of an audience. He’s usually like this, in truth, though today with a dedicated respect for his task. i ask him about that. “This is an achievement. Providing is primal.” A part of me hears this and scoffs, but the witness to this day is more measured, sees that truth. The efforts here demand the whole of a person. Even the repetitive plucking.

The farmer has draped his sheet of plastic indelicately in order to separate himself from the bloody, and now molting, dead bird on his lap. He has done everything today with his bare hands, and has already changed pants once, due to an abundance of blood. I guess the sheet is to save the new pants.

“Their first set of feathers” is what’s plucked now. It’s very boring, looks tedious, and sounds gross, like plastic velcro that isn’t densely packed enough. i entertain myself with the puppy (she did not witness the deaths this time, but she will be around it her whole life). When only down remains, the duck bodies are dipped in hot, melted wax and stripped of it. Who knew there would be something familiar for me in this day.

i am here on the ground, still bearing witness, writing as the sun wanes. The plucking goes on and on, and i am struck by the degree of labor yet again. “Do machines do this elsewhere?” “Yeah but the last feathers are always hand-plucked.” He talks about how much harder it will be to pluck the mallards—these are peking ducks. The puppy falls asleep on my foot, and the man waxing his bird draws my attention to it, “Starting to look less like an animal and more like a meal now, huh?” He’s not wrong. The skin and sinew of a familiar feast is now exposed, pale and muscled.

Pliers pluck the final pinfeathers as the sun goes down. The air gets cold and our party is relieved to return to the house, carrying meat that looks marketable. i am asked for the blow torch, which i hand over without receiving a please or thank you. Here i notice the toll taken by this kind of bodily labor on what might otherwise be a natural courtesy. Fatigue and focus, probably too that primal drive, have arrested the humanity of this project. (i suppose i could muse about humanity here, but i am only learning these things for the first time—there will be no judgment from me.) Whatever fluff could possibly be left of the feathers, but for the still-covered head, are blow-torched in seconds. The head gets a quick chop.

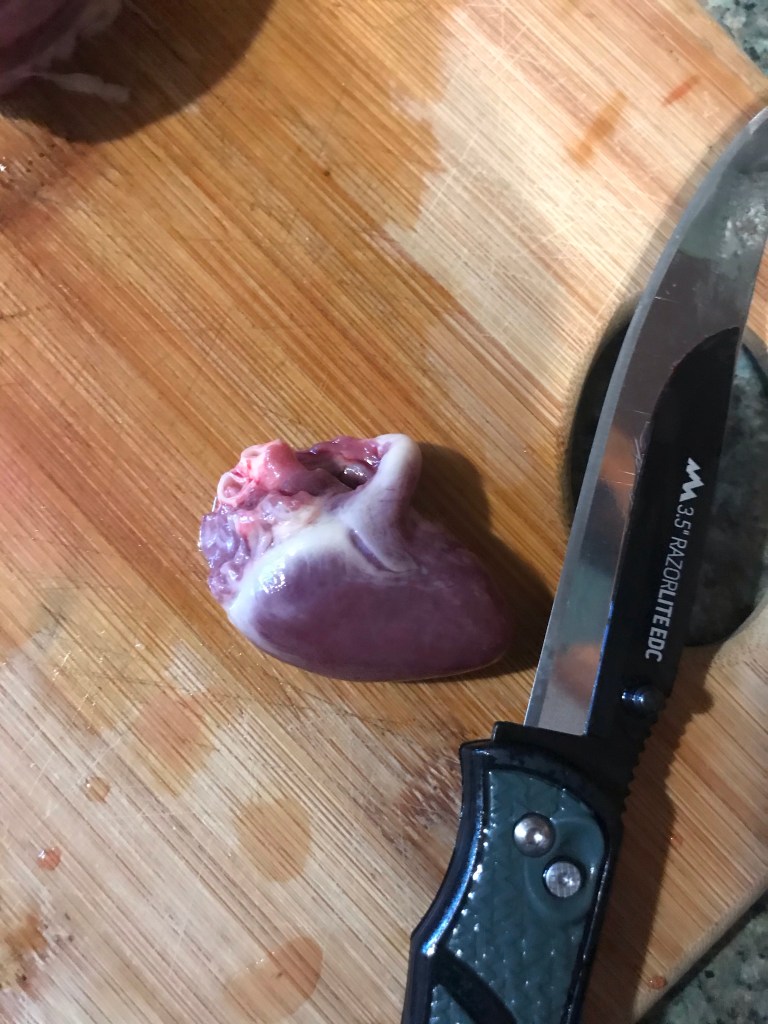

When the guts come out of the duck i find myself entranced by the beauty of the heart. i want to spend time drawing it, but it’s not mine. i settle for several photographs. i am overcome by the visible perfection of this small muscle. And it looks delicious, as if it might be brimming with favors toward good health. This is a bloody organ i am observing. i can’t help but notice how animal it feels to literally drool at raw meat. Primal, indeed.

Throughout the day there have been long stretches of silence, most often interrupted by some story or curiosity that has occurred to the farmer in the course of his killing. (At one point he starts belting out incorrect lyrics to a pop song i’m sorry i recognize and, comically, it’s the worst part of the day.) He tells me of air going through ducks as he cleans them, sometimes hitting “the quacker” just right. Sometimes a dead duck will quack, he explains, and it’s startling. He also tells me about hunters using those quackers to make duck calls for future hunts. Now he holds the noisemaker itself in bloodied hands. It looks like a fat, wet noodle with a tiny, slimy bellows, and seems too floppy for any further use. So, when he finds out i might repeat this particular hunting “fact,” this man does a bit of research and quickly debunks himself. i debate repeating the tale anyway—it just sounded so good. i am more than a little likely to insist on trying to force air through the next quacker.

The feet come off now, last, and a bird that lived this morning is finally just a piece of meat this evening. “Do you see that dense layer of fat?” The farmer uses a knife to point and it’s obvious even to me that this bird will be delicious. Every stage of this effort has been an achievement for the person who provides; milestones. Despite this, every step has also been wholly unceremonious. Part of me thinks of the song where the lady goes to the circus and wonders “is that all there is?” i didn’t expect much, but the even keel of the day has surprised me. There hasn’t been room for anything impractical, particularly not sentiment. Exhaustion will sneak up on me later, and i will wonder again at bearing witness to death. Was it difficult, in the end?

Only now, appraising meat that could look great in a butcher shop window, does this farmer allow himself to discuss the size and selling price of his ducks. He recognizes this shift in himself with interest, and says he will think about them again later as living creatures. So will i.

Wow. Such a vivid account. Sounds like it’s good to witness the process,

and to so clearly recount the experience. Nicely done!

LikeLike